By Crypto AM: Taking a Byte Out of Digital Assets with Jonny Fry

It is easy for asset managers to be complacent and forget that they are purely the managers of other people’s money. Whilst these managers believe they are acting in the best interest of their mutual fund holders perusing ESG practices, such unit holders are not able to vote on corporate matters nor enjoy shareholders perks.

There has been a trend to general disengagement between the actual shareholders and the boards of quoted companies since some forget whose money it is anyway. By offering digital versions of traditional assets, we can offer greater transparency and inclusiveness and hopefully more direct engagement with organisations and investors.

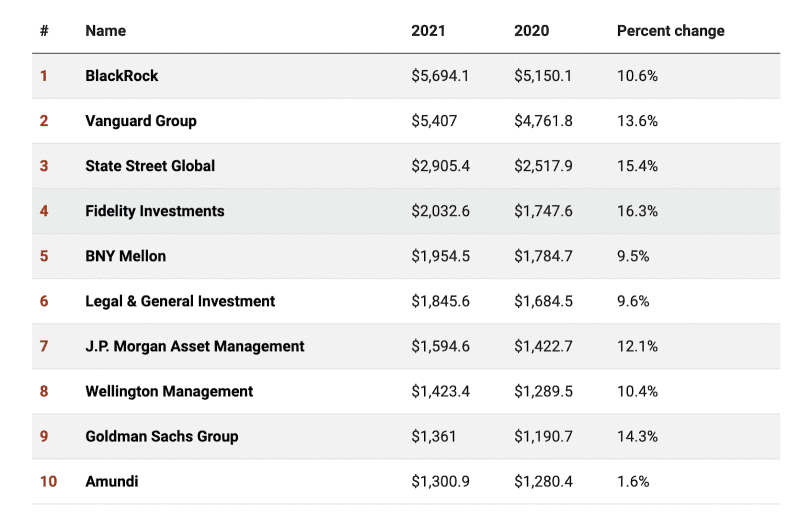

More than $112trillion of assets are held in funds globally. As the chart below indicates, there are a handful of asset managers who control huge pools of capital and make decisions on behalf of investors. Unfortunately, the percentage of registered shareholders who vote on quoted companies’ resolutions is low.

“The information gap is one of the biggest challenges to retail participation in proxy voting,” Gabe Rissman, co-founder of YourStake, is quoted as saying in a report by CNBC – YourStake being an ESG and socially responsible investing portfolio analysis and reporting tool for asset managers. Surely this is not right, as with the correct technology and right controls in place asset managers ought to embrace what their customers really want?

Managers ranked by total worldwide institutional assets under management

(assets in billions as of Dec. 31, 2021)

Source: Pensions and Investment

There has been a huge growth in funds dedicated to Environmental Social Corporate Governance (ESG)-conscious investors. Indeed, in just 2021, to the global fixed interest manager, PIMCO, there were over $1trillion ESG-labelled bonds issued.

Clearly there are many investors justifiably concerned about the environment and looking to ensure their money is invested into ESG-friendly businesses. The dilemma is that there are no global standards as to what is, and what is not, an ESG investment.

Measuring the ESG credentials of an organisation that has issued an equity or debt instrument is fraught with challenges. For example, do you not invest in petrochemical firms or, as a bank, not lend to them because they are mining/drilling fossil fuels? Yet, they are also investing $billions into renewable energy projects and some, such as the Norwegian firm, Statoil, have even changed their names to reflect the emphasis and long-term commitment they have to renewables.

Tesla is another example of a company which could be shunned by some ESG asset managers yet embraced by others. True, it is building electric cars but, in doing so, has decided to invest into Indonesia to mine nickel which, unsurprisingly, is being opposed to by environmentalists.

The European Securities and Markets Authority recently reported that:

- ESG funds are more oriented towards large cap stocks, and

- ESG funds are more oriented towards developed economies.

But does this mean there is yet another barrier for smaller and medium-sized companies to face when it comes to finding investors? Very often it is the SMEs which are able to be more ESG-responsible since their businesses are less complex and the management is able to have a better macro view of the business, its suppliers and its customers.

It is not simply that private investors don’t have the opportunity to vote about corporate matters related to the companies they own, but they are also losing out on shareholder perks. It is known that a number of quoted companies offer their shareholders perks such as benefits and rewards, often enabling shareholders to receive a discount off goods and services from the firms in which they hold shares. In the UK, Hargreaves Lansdown has a list of shareholder perks and GoBankingRates also has a list of quoted companies offering shareholder perks. Unfortunately, most asset managers either do not tell investors or are unable to pass on these perks to the holders of their mutual fund customers.

In January 2022, BlackRock’s CEO, Larry Fink, warned companies that his fund managers were looking to allocate capital needed “to step up efforts to tackle climate change”. Easy to say when you are personally worth $1billion, but certainly harder for those individuals and corporations struggling to survive.

Do asset managers’ customers really know what decisions fund managers are making on their behalf – agreeing the renumeration and option packages, for example, or whether or not to invest in a company based on random ESG criteria? Surely BlackRock and other global fund manager titans ‘looking after’ other peoples’ money need to find better ways in which to engage with their investors and, if possible, hand over more control when it comes to voting on corporate issues?

Furthermore, despite our so-called sophisticated stock markets and electronic trading, it is currently impossible to know who the shareholders are in any publicly quoted company on any stock exchange during normal working hours. It is only after the stock exchange has closed and the share registrars have tallied up all the buyers and sellers that this can be configured.

In all, it can present challenges to regulators and even those companies needing to ascertain which shareholders are eligible to vote or receive dividends. Hence the need to select a date for such activities since the relevant shareholder details are not available in real time. In a similar manner trades on UK stock exchanges took 10 business days to be settled.

In 2014, the London Stock Exchange moved from settling trades in three days to two days. In many other jurisdictions, settlement also takes two days, while in the US is looking to migrate to one day. But why not trade and settle in real time?

There is growing evidence of institutions looking to offer digitally wrapped e.g., digital equities, digital debt instruments, commodities, real estate, mutual funds etc. A good example of this is the recent announcement that the £532billion UK based fund manager Abrdn (formerly Standard Life Abderdeen plc) are investing in Archax a digital assets platform with a view to creating a digital wrapper around some of Aberdeen’s existing mutual funds. Russell Barlow, global head of alternatives at Abrdn, said: “Our view is that the next disruptive event will be the transfer from electronic trading to digital exchanges and trading through digital securities”.

Therefore, there is no reason why holders of income-producing investments such as property, shares, bonds etc, cannot receive their dividend/coupons/rent on a weekly basis. By using blockchain technology, it ought to be possible to increase levels of transparency so that unit holders cannot be granted the same privileges as shareholders, and therefore receive the perks and ability to vote on corporate matters.

Since one of the key objectives of many regulators is to treat customers fairly, then by having access to income monthly as opposed to every six months and offering the actual shareholders the ability to vote (not to mention the greater transparency of knowing who the shareholders or owners of a property/debt instrument are in almost real time) has to be attractive.

Indeed, could we see regulators, once they understand the transformational opportunities that digital assets provide, become champions of digital assets as opposed to being reluctant bystanders?

JF

The post Whose money is it anyway? How blockchain technology can give control back to investors appeared first on CityAM.