A new study has found that differences in the functional architecture of the brain are linked to appetite changes associated with depression. The findings have been published inJAMA Psychiatry.

Changes in appetite are common among individuals with depression. While some people may experience an increase in appetite and weight gain, others may have a decrease in appetite and lose weight. But little is known about the causes of these differences in symptoms within depression and how they can be specifically treated.

Identifying neural signatures of depression has proven difficult, possibly because of the contradictory nature of symptoms. The scientists behind the new study were interested in exploring whether the functional architecture of the brain’s reward system was linked to increases or decreases in appetite and weight among those with major depressive disorder.

“Initially, I was puzzled that there were numerous studies on group differences in reward processing or functional connectivity of the reward circuit comparing patients with depression and matched healthy controls that did not indicate a robust pattern across studies,” explained study author Nils B. Kroemer, an associate professor at the University of Bonn and director of the Neuroscience of Motivation, Action, and Desire Laboratory at the University of Tübingen.

“In light of the severe changes in reward function during a depressive episode, this is quite surprising.”

“Before researching this topic in depth, I was working on the regulation of the reward system, for example, by metabolic state and circulating hormones,” Kroemer said. “Such metabolic signals tune reward-related behavior according to demand and they can have rather strong effects on behavior. To me, it seemed counterintuitive to ignore the direction of appetite changes during depressive episodes if we want to understand differences in the reward system in patients with depression.”

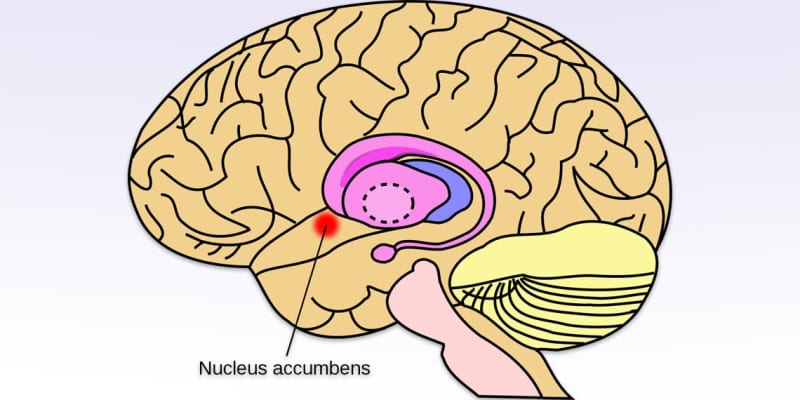

For their study, the researchers examined functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from the Marburg-Münster Affective Disorder Cohort Study. The analysis included 407 patients with major depressive disorder and 400 healthy controls. The researchers examined the brain function of participants at rest and recorded their psychological symptoms. Kroemer and his colleagues were particularly interested in the functional connectivity between the nucleus accumbens, one of the central regions in processing rewards, and other brain regions.

The researchers found that reduced connectivity between the reward system and the hypothalamus was associated with higher BMI. The hypothalamus is a small, almond-shaped region of the brain that serves as the control center for many vital functions. Among other things, it regulates body temperature, hunger, thirst, and fatigue. It also plays an important role in regulating hormone levels.

Importantly, differences in the functional architecture of the reward system were associated with specific appetitive symptoms. The researchers observed reduced functional connectivity between the reward system and the hippocampus, a region crucial to memory, among patients with depression who experienced a loss of appetite. Reduced appetite was also associated with reduced functional connectivity between the reward system and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in goal-directed and emotional behavior.

When there was an increase in appetite, on the other hand, the researchers observed a weaker connection between the reward system and the insular ingestive cortex and frontal operculum, regions where taste stimuli and bodily signals are processed.

The findings have important implications for potential treatments. In particular, the findings might help to develop more targeted therapies that directly address specific symptoms of depression.

“Appetite-related changes in depression require a deeper look because it might be easier to find specific treatment modules (e.g., targeted brain stimulation) for more fine-grained symptoms of depression,” Kroemer told PsyPost. “Depression is a heterogeneous disorder with many possible symptom profiles, and we may not be able to identify robust changes in the reward system if we ignore these marked differences in reward-related behavior by lumping all symptoms together.”

Interestingly, the researchers were unable to predict depression based on functional connectivity profiles. “I was surprised to see that we could not robustly classify whether a person is healthy or depressed based on the functional connectivity of the reward circuit,” Kroemer said. “It only worked once we considered the direction of changes in appetite, but this is often not done in case-control studies.”

As with any study, the new research also includes some limitations.

“There are two major limitations that call for future research,” Kroemer explained. “First, we investigated functional connectivity at rest and it would be beneficial to include tasks that robustly activate the reward circuit to substantiate our findings. Second, our study is cross-sectional so we need to investigate longitudinal changes in appetite across depressive episodes, and, ideally, after remission to separate trait effects (i.e., durable inter-individual differences) vs. state effects (i.e., specific changes during a depressive episode).”

“I hope there will be more funding for innovative research on mental disorders,” Kroemer added. “If we look at the burden on health, there is still less funding for research on mental disorders compared to many other disorders.”

The study, “Functional Connectivity of the Nucleus Accumbens and Changes in Appetite in Patients With Depression“, was authored by Nils B. Kroemer, Nils Opel, Vanessa Teckentrup, Meng Li, Dominik Grotegerd, Susanne Meinert, Hannah Lemke, Tilo Kircher, Igor Nenadić, Axel Krug, Andreas Jansen, Jens Sommer, Olaf Steinsträter, Dana M. Small, Udo Dannlowski, and Martin Walter.