A Two-Part Look at: 1. Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, and 2. How They Apply to What’s Happening Now

Now that we are at the beginning of a new year, it seems appropriate to review the timeless and universal mechanics of money and debt cycles and the principles for dealing with them, and then to apply these to what’s happening now. I will do the first of these today and the second in a week or two.

Q4 2022 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Principles For Navigating Big Debt Crises

In this post, I am giving a highly condensed version of what I described in my book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, which is an extension of the study I did of all big debt cycles in all major countries over the last 100 years.

It lays out how I see the mechanics working to produce money-credit-debt-market-economic cycles, so it is helpful for understanding the one we are going through now.

This template has also been very helpful in my and Bridgewater’s investment decision making, including during the 2008 financial crisis when it allowed me and Bridgewater to both navigate the crisis well and provide some helpful advice to policy makers.

I wrote the book in 2018 at the suggestion of former Treasury Secretaries Henry Paulson and Timothy Geithner and Fed Chair Ben Bernanke because we went through the 2008 financial crisis together in our different roles and they thought that on the 10th anniversary of the crisis it was important to share the lessons of that crisis in this book and other books.

In its first 65 pages there is a complete summary of the mechanics and principles. I believe the most important pages to read now are Pages 16 to 38, which explain the seven stages of the typical cycle, most importantly how to identify them and how to handle them.

That is because identifying them and knowing how to move when they move is very important. The rest of the book delves into all the different cases, which you can skip or wade into in depth as you like.

In this post, I am going to describe how I see the mechanics and principles of the money-credit-debt-market-economic cycles working in fresh words as it applies to what’s now happening. In a week or two, I will look at the specifics of what has been happening, putting it in the context of this template.

While there is too much for me to cover in a detailed and comprehensive way in the limited space I have here, I will pass along the most important points about how the debt dynamic works in an imprecise way to get across the most important concepts.

Also, for readers who want to get just the most important concepts in the quickest possible way,I will put the most important points in bold so you can read just that.

How The Machine Works And Principles For Dealing With It

In a nutshell, the debt dynamic works like a cyclical perpetual-motion machine with the most important cause/effect relationships that drive it working in essentially the same way through time and across countries.

While of course changes over time and differences between countries exist, they are comparatively unimportant in relation to the timeless and universal mechanics and principles that are far less understood than they should be.

For that reason, I will focus on these most important timeless and universal mechanics and principles. To convey them in brief I will explain just the major ones in a big-picture, simplified way rather than a detailed and precise way.

In this big-picture, simplified model of the money-credit-debt-markets-economic machine, the following describes the major parts and the major players and how they operate together to make the machine work.

There are five major parts that make up my simplified model of this machine. They are:

1. goods, services, and investment assets,

2. money used to buy these things,

3. credit issued to buy these things, and

4. debt liabilities (e.g., loans) and

5. debt assets (e.g., deposits and bonds) that are created when purchases are made with credit.

There are four major types of players in this model. They are:

1. those that borrow and become debtors that I call borrower-debtors,

2. those that lend and become creditors that I call lender-creditors,

3. those that intermediate the money and credit transactions between the lender-creditors and the borrower-debtors that are most commonly called banks, and

4. government-controlled central banks that can create money and credit in the country’s currency and influence the cost of money and credit.

If you understand how these major parts work and the motivations of these players in dealing with them, you will understand how the machine works and what is likely to happen next, so let’s get into that.

As mentioned, goods, services, and investment assets can be bought with either money or credit.

Money, unlike credit, settles the transaction. For example, if you buy a car with money, after the transaction, you’re both done. What has constituted as money has changed throughout history and across currencies.

Since 1971, it has been simply what central banks printed and provided in the form of credit. Money, unlike credit, at this time can only be created by central banks [1] and can be created in whatever amounts the central banks choose to create.

Credit, unlike money, leaves a lingering obligation to pay and can be created by mutual agreement of any willing parties. Credit produces buying power that didn’t exist before, without necessarily creating money.

It allows borrowers to spend more than they earn, which pushes up the demand and prices for what is bought over the near term while creating debt that requires the borrowers, who are now debtors, to spend less than they earn when they have to pay back their debts. This reduces demand and prices in the future, which contributes to the cyclicality of the system.

Because debt is the promise to deliver money and central banks determine the amount of money in existence, central banks have a lot of power. Though not proportionately, the more money that’s in existence, the more credit and spending there can be; the less money in existence, the less credit and spending there can be.

Credit-debt expansions can only take place when both borrower-debtors and lender-creditors are willing to borrow and lend, so the deal must be good for both. Said differently, because one person’s debts are another’s assets, it takes both borrower-debtors and lender-creditors to want to enter into these transactions for the system to work.

However, what is good for one is quite often bad for the other. For example, for debtors to do well, interest rates can’t be too high, while for creditors to do well, interest rates can’t be too low.

If interest rates are too high for borrower-debtors, they will have to slash spending or sell assets to service their debts, or they might not be able to pay them back, which will lead markets and the economy to fall.

At the same time, if interest rates are too low to compensate lender-creditors, they won’t lend and will sell their debt assets, causing interest rates to rise or central banks to print a lot of money and buy debt in an attempt to hold interest rates down. This printing/buying of debt will create inflation, causing a contraction in wealth and economic activity.

Over time environments will shift between those that are good and bad for lender-creditors and borrower-debtors, and it is critical for everyone who is involved in markets and economies in any way to know how to tell the difference.

While this balancing act and the swings between the two environments take place, sometimes conditions make it impossible to achieve a good balance. That causes big debt, market, and economic risks. I will soon describe what conditions produce these risks, but before I do I want to explain the other players’ motivations and how they try to act on them.

Banks [2] are the intermediaries between lender-creditors and borrower-debtors, so their motivations and how they work are important too. In all countries for thousands of years up to now, banks did essentially the same thing, which is borrow money from some and lend it to others, making money on the spread to generate a profit.

How they do this creates the money-credit-debt cycles, most importantly the unsustainable bubbles and big debt crises. Banks are motivated to make profits by lending out a lot more money than they have, which they do by borrowing at a cost that is lower than the return they take in from lending.

That works well for the society and is profitable when those who are lent money use it productively enough to pay back their loans and make the bank a profit—and when those the banks borrowed from don’t want their money back in amounts that are greater than what the banks actually have.

However, when the loans aren’t adequately paid back or when those that the banks borrowed from want to get more of the money they lent to the banks than the banks have to give them, debt crises happen.

Over the long run, debts can’t rise faster than the incomes that are needed to service the debts, and interest rates can’t be too high for borrower-debtors or too low for lender-creditors for very long.

If debts keep rising faster than incomes and/or interest rates are too high for borrower-debtors or too low for lender-creditors for too long, the imbalance will topple into a big market and economic crisis. Said differently, big debt crises come about when the amounts of debt assets and debt liabilities become too large relative to the amount of money in existence and/or the amounts of goods and services in existence. For that reason, it pays to watch these ratios.

Central banks came into existence to smooth these cycles, most importantly by handling big debt crises. Until relatively recently (e.g., 1913 in the United States) there weren’t central banks, and money that was in private banks was typically either physical gold or silver or paper certificates to get gold and silver.

Throughout these times, there were boom-bust cycles because borrower-debtors, lender-creditors, and banks went through the credit-debt cycles I just described. These cycles turned into big debt and economic busts when too many debt assets and liabilities led to creditor “runs” to get money from debtors, most importantly the banks.

These runs produced debt-market-economic collapses that eventually led governments to create central banks to lend money to banks and others when these big debt crises happened. Central banks can also smooth the cycles by varying interest rates and the amount of money and credit in the system to change the behaviors of borrower-debtors and lender-creditors.

Where do central banks get their money from? They “print” it (literally and digitally), which, when done in large amounts, alleviates the debt problems because it provides money and credit to those who desperately need it and wouldn’t have had it otherwise. But doing so also reduces the buying power of money and debt assets and raises inflation from what it would have been.

Central banks want to keep debt and economic growth and inflation at acceptable levels. In other words, they don’t want debt and demand to grow much faster or slower than is sustainable and they don’t want inflation to be so high or so low that it is harmful.

To influence these things, they raise interest rates and tighten the availability of money or they lower interest rates and ease the availability of money, which influences creditors and debtors who are striving to be profitable.

The greater the size of the debt assets and debt liabilities relative to the real incomes being produced, the more difficult the balancing act is, so the greater the likelihood of a debt-caused downturn in the markets and economy.

Because borrower-debtors, lender-creditors, banks, and central banks are the biggest players and drivers of these cycles, and because they each have obvious incentives affecting their behaviors, it is pretty easy to anticipate what they are likely to do and what is likely to happen next.

When debt growth is slow, economies are weak, and inflation is low, central bankers will lower interest rates and create more money and credit which will incentivize more borrowing and spending on goods, services, and investment assets which will drive the markets for these things and the economy up. At such times, it is good to be a borrower-debtor and bad to be a lender-creditor.

When debt growth and economic growth are unsustainably fast and inflation is unacceptably high, central bankers will raise interest rates and limit money and credit which will incentivize more saving and less spending on goods, services, and investment assets.

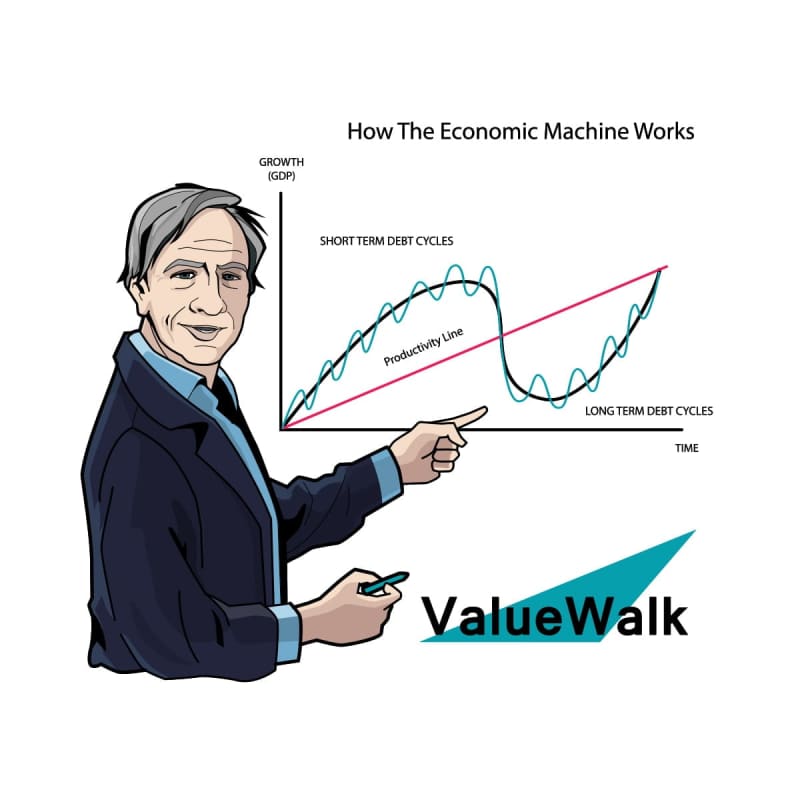

This will drive the markets and economy down because it’s then better to be a lender-creditor-saver than a borrower-debtor-spender. This dynamic creates short-term debt cycles (also known as business cycles) that have typically taken about seven years, give or take three years.

In almost all cases throughout history, over time these short-term debt cycles have added up to create long-term debt cycles that have lasted about 75 years, give or take about 25 years.

The stimulation phases of these cycles create bull markets and economic expansions and the tightening phases create bear markets and economic contractions. For a more complete review of these cycles and key indicators read Pages 16 to 65 in the book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises.

Why don’t central bankers do a better job than they have been doing in smoothing out these debt cycles by better containing debt so it doesn’t reach dangerous levels? There are four reasons:

1. Most everyone, including central bankers, wants the markets and economy to go up because that’s rewarding and they don’t worry much about the pain of paying back debts, so they push the limits, including becoming leveraged to long assets until that can’t continue because they have reached the point that debts are too burdensome so they have to be restructured to be reduced relative to incomes.

2. It is not clear exactly what risky debt levels are because it’s not clear what will happen that will determine future incomes.

3. There are opportunity costs and risks to not providing credit that creates debt.

4. Debt crises, even big ones, can usually be managed to reduce the pain of them to acceptable levels.

Debt isn’t always bad, even when it’s not economic. Too little credit/debt growth can create economic problems as bad or worse than too much, with the costs coming in the form of forgone opportunities.

That is because 1) credit can be used to create great improvements that aren’t profitable that would have been forgone without it, and 2) the losses from the debt problems can be spread out to be not intolerably painful if the government is in control of the debt restructuring process and the debt is in the currency that the central bank can print.

When debt assets and liabilities become too large relative to incomes and debt burdens have to be reduced, there are four types of levers that policy makers can pull to reduce the debt burdens:

1. austerity (i.e., spending less),

2. debt defaults/restructurings,

3. the central bank “printing money” and making purchases (or providing guarantees), and

4. transfers of money and credit from those who have more than they need to those who have less.

Policy makers typically try austerity first because that’s the obvious thing to do and it’s natural to want to let those who got themselves and others into trouble bear the costs. This is a big mistake.

Austerity doesn’t bring debt and income back into balance because one person’s debts are another person’s assets so cutting debts cuts investors’ assets and makes them “poorer” and one person’s spending is another person’s income so cutting spending cuts incomes.

For that reason cuts in debts and spending cause a commensurate cut in net worths and incomes, which is very painful. Also, as the economy contracts, government revenues typically fall at the same time as demands on the government increase, which leads deficits to increase.

Seeking to be fiscally responsible at this point, governments tend to raise taxes which is also a mistake because it further squeezes people and companies. More simply said, when there is spending that’s greater than revenues and liquid liabilities that are greater than liquid assets, that produces the need to borrow and sell debt assets, which, if there’s not enough demand for, will produce one kind of crisis (e.g., deflationary) or another (e.g., inflationary).

The best way for policy makers to reduce debt burdens without causing a big economic crisis is to engineer what I call a “beautiful deleveraging,” which is when policy makers both 1) restructure the debts so debt service payments are spread out over more time or disposed of (which is deflationary and depressing) and 2) have central banks print money and buy debt (which is inflationary and stimulating).

Doing these two things in balanced amounts spreads out and reduces debt burdens and produces nominal economic growth (inflation plus real growth) that is greater than nominal interest rates, so debt burdens fall relative to incomes.

If done well, the deflationary and depressing reduction of debt payments and the inflationary and stimulating printing of money and buying of debt by the central banks balance each other. In the countries I studied, all big debt crises that occurred with the debts denominated in a country’s own currency were restructured quickly, typically in one to three years.

These restructuring periods are periods of great risk and opportunity. If you want to learn more about these periods and processes, they are explained more completely in Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises.

How These Mechanics Have Played Out From 1945 Until Now

As World War II was ending, a new world monetary system began in 1944. It was a US dollar-based system because the US was the richest country (it had most of the world’s gold and gold was money at the time), it was the world’s dominant economic and trading power, and it was the world’s dominant military power.

For those reasons, a US dollar credit system was created in a way that tied debt assets and liabilities to gold, and other countries tied their currencies to the dollar.

From 1945 to 1971 there were six short-term money-credit-debt-economic cycles in which the United States central government and central bank created more debt asset claims on the gold than the US had gold in the bank.

As had happened repeatedly over thousands of years, the much larger financial claims on the money than the actual money in the bank led to a run on the central bank to get the money (i.e., the gold), which led the US in 1971 to default on its promises to allow holders of debt assets to turn them in for the money (gold).

In other words, during the whole 1945-71 period the Federal Reserve guided this credit cycle in a way that created many more debt asset claims on the gold-money than there was in the government’s bank so the government had to default on its promises to provide gold-money.

That led to the debt restructuring that took the form of a US government debt default and the creation of a lot of money, credit, and debt which led to the devaluations of money and large inflation around the world.

All that should not have been a surprise to students of economic history because history has shown that when governments are faced with this choice of how to deal with the excessive debts and the need to bring them down relative to incomes, this process is the least painful one, though it is still painful.

That is why, in the end of all big debt cycles, all currencies have either been devalued or destroyed. Since 1971, we have been in what is called a fiat monetary system in which there are no constraints on governments’ abilities to create money and credit.

For reasons explained more completely in Chapters 3 and 4 of my book Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order, throughout history hard-money-linked monetary systems created too much debt, eventually leading to debt and economic crises and soft money—and quite often the creation of fiat monetary systems, which also created too much debt that led to money and debt devaluations which led to very tight money and often the return of hard-money systems, until these broke down, and so on repeatedly.

The money and debt devaluations of 1971 and the newly gained free ability of central banks to create money, credit, and debt to fight economic stagnation led to the massive stagflation of the 1970s.

Naturally the pendulum swung so that when late-1970s inflation was perceived as a bigger problem than weak or negative growth, the Fed produced a tightening of monetary policy in 1979-82. This flipped things so that it was much better to be a lender-creditor than a borrower-debtor and downturns in markets and economies followed. As explained, similar versions of this cycle have happened repeatedly for the same reasons throughout history.

In the interests of time and space I won’t now take you through all that has happened since 1980, but I will give a quick summary to show that the pattern has continued until now: short-term debt cycles adding up to greater and greater levels of debt assets and debt liabilities that constitute the big long-term debt cycle.

Normally when central banks want to be stimulative, they lower interest rates and/or create a lot more money and credit, which creates a lot more debt. This both extends the expansion phase of the cycle and makes the debt asset and debt liability balance more precarious.

That is what happened between 1980 and 2008. During that time, debts continued to rise relative to incomes as every cyclical peak and every cyclical trough in interest rates was lower than the one before it until interest rates hit 0% in 2008.

History shows us that when central banks can’t lower interest rates anymore and want to be stimulative, they print money and buy debt, especially government debt. That gives debtors, most importantly governments, money and credit to prevent them from defaulting and allows them to continue to borrow to spend more than they are earning, so their debts can continue to increase.

That is what has been happening since 2008. At such times, central banks are making up for the shortfall in the private sector’s demand for debt. They are happy to do so even if it doesn’t make economic sense because their objective is to stabilize markets and economies, not to make a profit.

During this part of the big debt cycle, central banks become the big buyers of debt and they become the big owners of debt (the big creditors) rather than private investors. Because central banks don’t mind having losses from holding the debt that has reduced in value and because they don’t worry about getting squeezed, they can continue to prevent a debt crisis by printing money and buying debt.

They let their balance sheets and income statements deteriorate in order to protect the private sector’s income statements and balance sheets. This process is called debt monetization. This dynamic has repeatedly taken place throughout time and across countries, and it has been true from 2009 until recently with each cyclical stimulation by central banks creating money and credit to buy debt larger than the one before it.

One can see that occur via changes in the central banks’ balance sheets by looking at their holdings of debt assets that were acquired by providing those who sold the debt assets to central banks with cash and credit. In the United States, Europe, and Japan, they own roughly 20%, 30%, and 40% of the government debt, respectively, and roughly 10%, 10%, and 20% of the total debt, respectively.

While in my next piece that I will put out in a week or two I will show what happened and what is now happening, my main goal of this piece has been to explain how the machine works. I especially want to show you that the big money-credit-debt cycle that we are in is taking place in the same basic way as past cycles have taken place for thousands of years with logical cause/effect relationships driving them.

The only important difference between today’s money (which is now fiat money) and prior monies (which were not fiat monies, such as that in the 1945-71 period) is the link to hard currency isn’t there. That means that central banks can now more freely create money and credit than in the past.

By the way, fiat monetary systems have existed throughout history, so studying them provides invaluable lessons of how they work that provide clues for how the one we are in will transpire.

What hasn’t changed through these shifts in monetary systems over the millennia—and hasn’t been eliminated as a problem—is the creation of unsustainably big debt liabilities and assets relative to the amounts of money, goods, services, and investment assets in existence, which can lead to a run for the money and the goods and services that have intrinsic value.

Because the only value of debt assets and other financial assets is to buy goods and services, if the holders of those financial assets actually tried to convert these assets back into money and goods and services, they would see that they couldn’t get the buying power they believe exists which could cause a run that’s like a bank run.

For that reason there remains the risk that those who are holding financial assets will turn them in for money to buy goods and services which would cause either inflationary spirals or severe economic weakness, depending on how much the central bank tries to fight the economic contraction effects by printing money and making credit easily available.

While central banks can more easily and flexibly print money and give it to debtors to alleviate the debt problems and give spenders the ability to spend in a fiat monetary system, it should be noted that their doing so doesn’t eliminate the rises in debt assets and debt liabilities that become excessive and produce debt crises.

My examination of past cycles, including those in fiat currencies, shows the debt cycle dynamics I described, including very big debt crises, always existed in virtually all countries. I see no reason to believe they will stop.

On the contrary, debt assets and debt liabilities are now very high and still rising, so it looks more likely that most economies’ central banks, most importantly the US’s Fed, Europe’s ECB, and Japan’s BoJ, are approaching the limits in their abilities to continue the money-credit-debt expansions that have been true throughout our lifetimes.

To repeat, when there are big debt crises, central banks have to choose between keeping money “hard,” which will lead debtors to default on their debts which will lead to deflationary depressions, or making money “soft” by printing a lot of it which will devalue both it and debt.

Because paying off debt with hard money causes such severe market and economic downturns, when faced with this choice central banks always eventually choose to print and devalue money. For the case studies see Part 2 of Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises. Of course, each country’s central bank can only print that country’s money, which brings me to my next big point.

If debts are denominated in a country’s own currency, its central bank can and will “print” the money to alleviate the debt crisis. This allows them to manage it better than if they couldn’t print the money, but of course it also reduces the value of the money.

I have only a few remaining points and then we are done.

Debt crises are inevitable. Throughout history only a very few well-disciplined countries have avoided debt crises. That’s because lending is never done perfectly and is often done badly due to how the cycle affects people’s psychology to produce bubbles and busts.

Most debt crises, even big ones, can be managed well by economic policy makers and can provide investment opportunities for investors if they understand how they work and have good principles for navigating them well.

In summary and to reiterate:

1. Goods, services, and investment assets can be produced, bought, and sold with money and credit.

2. Central banks can produce money and can influence the amount of credit in whatever quantities they want.

3. Borrower-debtors ultimately require enough money and low enough interest rates for them to be able to borrow and service their debts.

4. Lender-creditors require high enough interest rates and low enough default rates from the debtors in order for them to get adequate returns to lend and be creditors.

5. This balancing act becomes progressively more difficult as the sizes of the debt assets and debt liabilities increase relative to the incomes.

6. A “beautiful deleveraging” can be engineered by central governments and central banks to reduce debt burdens if the debt is in their own currencies.

7. Over the long term, being productive and having healthy income statements (i.e., earning more than one is spending) and healthy balance sheets (i.e., having more assets than liabilities) are the markers of financial health.

8. If you know where in the credit-debt cycle each country is and how the players are likely to behave, you should be able to navigate these cycles pretty well.

9. The past is prologue.

As always, I’m not certain of anything, I am putting these thoughts out for your consideration to take or leave as you like, and I hope that you find them helpful.

Footnotes

[1] Bitcoin is an example of an attempt to create a private version of money using blockchain distributed ledger technology.

[2] For simplicity I am using the word “banks” to describe all financial intermediaries that take on financial liabilities to get higher returns in financial assets.

Bridgewater Daily Observations is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients.

Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others.

Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.

Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision.

Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations.

Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or over compensated for the impact of certain market risk factors.

Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate.

Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction.

No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed.

Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.

Article by Ray Dalio, via LinkedIn