By Crypto AM: Taking a Byte Out of Digital Assets with Jonny Fry

One of the earliest forms of money stones were used by Pacific islanders. A monetary system, based on credit, was developed by communities which knew who owned what stones and where the stones were.

The rai (or fei) stones themselves did not move when traded, but remained in situ. Some were even hidden from view as they were under the sea.

It is believed that, back then, the rai stones were quarried and afterwards transported by canoe over 500 kilometres.

Given the difficulty of quarrying by hand and the challenges of transporting such large lumps of limestone, the Yaps placed great value on the stones. As a result, they became the backbone of a very sophisticated way of exchanging value.

The stones came in a variety of sizes, from those you could hold in your hand to huge stones that had a hole carved in them to allow for poles of wood to be inserted so they could be lifted. It is believed “that a stone three hand-lengths across was worth one pig between eighty and one hundred pounds (36-45 kilograms).”

A stone of this size was also said to be enough to purchase one thousand coconuts, and a stone six feet (1.8 metres) across could buy a large canoe. In effect, the rai stones were valuable because of their scarcity and the amount of labour that was required to quarry and transport them. Centuries later, and the use of these stones continues today as a form of payment for dowries or purchases of land.

Such a concept was at the core of the ‘labour theory of value’ (LTV) which Scottish economist and moral philosopher, Adam Smith, wrote about in The Wealth of Nations. LTV was used as a way to explain how to value different commodities dependent on the amount of labour it takes to create/mine them.

With this in mind, the Yapese had, in effect, created a decentralised community balance sheet premised on the value of rai stones and where everyone knew who owned what. Moreover, no money changed hands. Instead, the value of the transaction was based on the rai stones, yet the stones themselves did not need to be moved.

In relation to LTV, the rai stones could be seen as representing labour and, furthermore, because the Yapese people valued these stones, the stones could arguably be seen as a store of value which for centuries were then the basis of their monetary system.

Notably, this monetary system did not require intermediaries and did not rely on a central governing entity. Additionally, unlike most so-called ‘sophisticated’ central bankers, who seem to create money out of thin air simply by printing more, the supply of rai stones was restricted by the ability to quarry and transport more.

So, in many ways, the rai stones are not dissimilar to Bitcoin today; instead of labour, consider the amount of computing power or the average cost of mining a Bitcoin as a proxy for what the value of that Bitcoin ought to be.

Decentralised = not knowing the actual location, with no intermediaries. Echoes of Bitcoin?

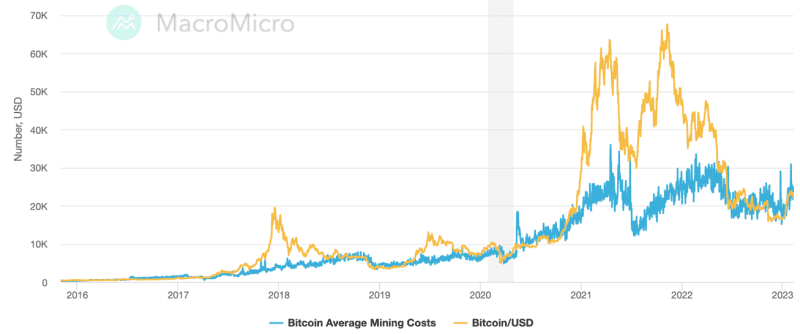

Historically, it would seem that there has been a close correlation between the average cost of creating a Bitcoin and the actual price of a Bitcoin. Yes, there have been times when the price of Bitcoin has far exceeded the cost, but currently there is an argument that Bitcoin is undervalued and ought to increase in price.

The price of BTC v the cost of mining a BTC…

Source: Macromicro.me

Could Rai stones, the monetary system that was used in remote Pacific islands for centuries, and Bitcoin’s price (based on the costs of mining) be used to determine the value of Bitcoin?

Looking at it a different way, the cost of ‘the proof of work’ (a concept used to describe the way a Bitcoin is created/mined) will alter depending on how hard it is to mine a Bitcoin and also the cost of electricity to power the computers.

Remember, too, that the number of Bitcoins halves every 210,000 blocks (which happens typically every four years). This means every four years the average price to create a Bitcoin becomes more expensive and so, in theory, this drives up the price of Bitcoin – assuming the demand for Bitcoin remains the same. Many argue that Bitcoin has no intrinsic value as it is not backed by anything, yet surely its value is driven by its scarcity and the difficulty/cost of mining?

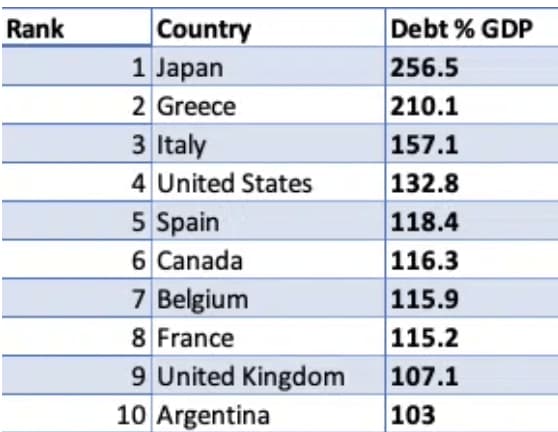

But one may well ask, what are fiat currencies backed by? Just look at the amount of debt that many countries now have – what are the $, £ Yen € backed by since most have greater debts than their GDPs? Yes, the below data is out of date but, unsurprisingly, given the sheer volume of debt that most countries have created in the last year or so these debts to GDP figures have typically deteriorated.

The debt of selected countries…

Bitcoin’s price will be influenced by a wide variety of factors such as supply and demand which are, themselves, often determined by sentiment towards this asset.

The cost of mining can impact the supply of new Bitcoins, but this may not necessarily drive the price directly or predictably. Other factors such as global economic conditions and investor and regulatory developments can also play a significant role in determining the price of Bitcoin.

Indeed, recently there has been a closer correlation between the price of technology shares and Bitcoin’s price. Nevertheless though, just maybe we can learn a lesson or two from the Pacific islanders and their rai stones as to how to determine if now is the time, or not, to buy Bitcoin.

The post Can Bitcoin’s price be based on stones? appeared first on CityAM.