A new study of patients with glaucoma in Russia reported a strong association between the level of retinal ganglion cell loss and the severity of depression symptoms. Loss of ganglion cells that happens as the result of glaucoma compromises the perception of light and thus results in deterioration of eyesight quality. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Glaucoma is a group of eye conditions that harm the optic nerve, which sends visual information from the eye to the brain. Increased pressure within the eye, known as intraocular pressure, is often associated with this damage. If left untreated, glaucoma can lead to vision loss and, in severe cases, permanent blindness.

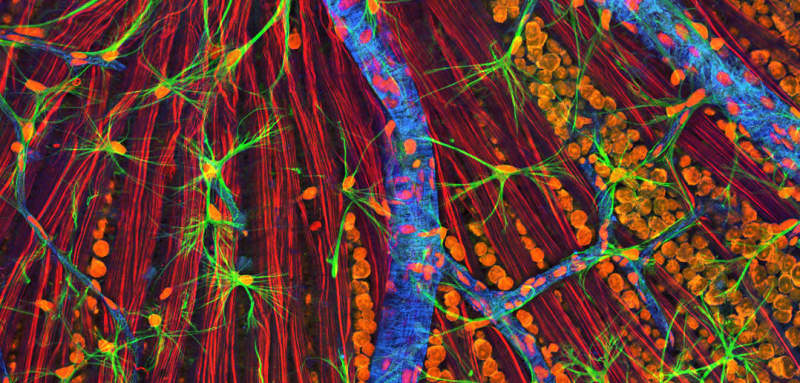

The retinal ganglion cells are a crucial part of the optic nerve. They are neurons located in the innermost layer of the retina and receive visual input, converting it into nerve impulses that are transmitted to the brain through the optic disc. In glaucoma, the increased pressure within the eye can cause mechanical stress on these cells, leading to their degeneration and loss.

Being able to see daylight is important for sleep and mood. Studies have found that people with glaucoma are more likely to experience mood changes and cognitive difficulties. A study in Mexico from 2021 reported that individuals with glaucoma have 10 times higher rates of depression symptoms compared to the general population.

Study author Denis Gubin and his colleagues wanted to examine whether this increased risk of depression in individuals suffering from glaucoma can be attributed to the loss of retinal ganglion cells. They used a non-invasive imaging technique called optical coherence tomography to capture detailed images of the retina. They also used a diagnostic test called pattern electroretinogram to assess the electrical responses of the retina i.e., the activity of retinal ganglion cells, to visual stimuli, particularly patterned stimuli such as checkerboard patterns.

The study included 115 patients diagnosed with glaucoma. They were required to have good visual acuity either with or without correction, a transparent eye lens and no pathology of the macular region of the retina.

The participants underwent assessments for depression symptoms, preferred sleep patterns, and eye health. The researchers evaluated the damage to retinal ganglion cells, the functionality of these cells, eye pressure, and other factors. They also analyzed saliva samples and genetic information.

The results showed that the more damage there was to retinal ganglion cells and the more advanced the glaucoma, the more severe the symptoms of depression. Participants with more severe depression symptoms had greater damage to retinal ganglion cells and lower functionality of these cells. Depression symptoms were also associated with sleep patterns, sleep duration, and age, regardless of gender.

The analysis of saliva samples and genetic information did not show a direct association between depression symptom severity and melatonin levels or genetic variations. However, patients with a specific genetic variant and advanced glaucoma tended to have more severe depression symptoms.

The researchers concluded that the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells is linked to depression scores, especially when the overall loss exceeds 15%. The study suggests that the loss of these cells in advanced glaucoma may affect non-visual processes related to light sensitivity and lead to mood disturbances.

While the study provides insights into the connection between eye health and depression, it has some limitations. The study design does not allow us to determine cause-and-effect relationships. Additionally, the researchers did not consider the participants’ history of mood disorders, so it remains unclear whether depression symptoms developed as glaucoma progressed or were present before the disease started.

The study, “Depression scores are associated with retinal ganglion cells loss”, was authored by Denis Gubin, Vladimir Neroev, Tatyana Malishevskaya, Sergey Kolomeichuk, Germaine Cornelissen, Natalia Yuzhakova, Anastasia Vlasova, and Dietmar Weinert.