By Chris Dorrell

As the dust settles on Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement, it has become increasingly clear that the Chancellor has taken a big bet.

Hunt has effectively banked the windfall from higher inflation, which has boosted tax receipts, without being completely honest about the spending cuts that the government will have to make after the next election.

On the Treasury’s current spending plans, non-ringfenced departments are set for areal terms spending cut on par with the years of austerity under Cameron and Osborne.

Many economists have said this is completely unrealistic. Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), said the spending plans were “questionable, if not plain implausible”.

But its worth acknowledging the fiscal bind the government finds itself in.

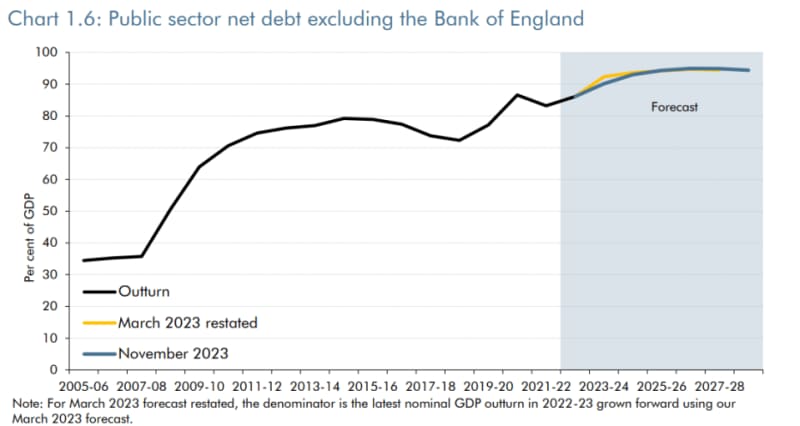

Even including Hunt’s tax cuts, the OBR forecast that tax will rise to around 38 per cent of national income by the end of this parliament. And yet debt is projected to remain comfortably above 90 per cent of GDP at the end of the forecast period.

In other words, debt remains stubbornly high even as the tax burden rises significantly.

The only way out of this fix is to improve the UK’s trend growth rate, which has been significantly lower since the financial crisis. Higher growth boosts tax receipts and lowers spending on welfare, strengthening the government’s fiscal position.

The question then is not so much whether the Chancellor has spent tomorrow’s money today (answer: he has), but whether spending tomorrow’s money will help break the trend of low growth.

The initial assessment is not particularly positive.

There were three important measures taken by the Chancellor yesterday: a 2p cut to the National Insurance rate; making permanent the full expensing of capital investment; and introducing measures to encourage people back into work

The measures cost around £18bn, making it the third largest discretionary fiscal loosening on the Treasury’s scorecard since 2010.

But the OBR forecast that the combined impact of these measures would provide a “modest boost” to output of 0.3 per cent in five years.

Is the Chancellor getting his money’s worth?

Speaking to reporters after the forecast, David Miles, member of the Budget Responsibility Committee, said “it’s actually very difficult for the government in a relatively short period, like a few years, to make a meaningful effect on growth”.

“To increase the underlying supply potentially the UK economy is a big task,” he said, pointing out that the full impact of the policies would only be felt long after the end of the forecast period.

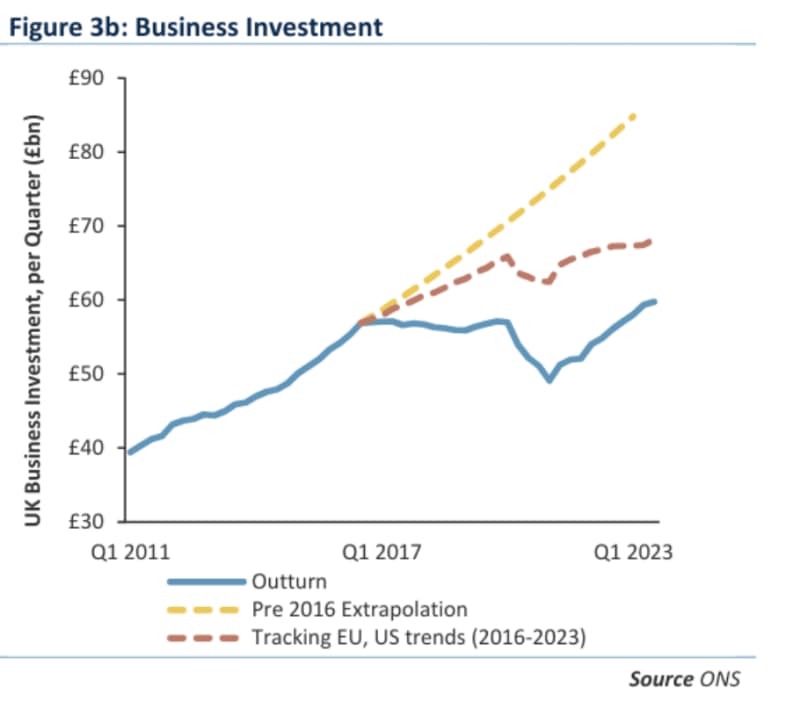

A large part of the UK’s sluggish performance and poor productivity growth comes from its low rate of investment. Compared to other G7 nations, investment makes up a much lower proportion of GDP and has been more or less flat since Brexit.

“A perennial problem for the economy has been low investment,” Gerard Lyons, chief economic strategist at Netwealth commented.

Hunt hopes that by making the full expensing of capital investment permanent, a move he described as the “largest business tax cut in modern British history“, businesses will be incentivised to invest more.

The OBR estimates that the measure will lift the overall capital stock in 2028-29 by 0.2 per cent. This is a permanent – albeit relatively small – improvement to the supply side of the economy.

“Hunt hopes this, along with his overhaul of UK ISAs and pension reform, will go some way in picking up UK business investment growth off the floor,” analysts at Capital Economics said.

Hunt’s back to work reforms meanwhile are expected to raise employment by 50,000 and hours worked by 28,000. This has become an increasingly important issue as forecasts suggest that inflation is likely to remain persistent, largely due to a tight labour market.

“Boosting labour market participation would help the country economically,” Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK said. But she said other measures, such as childcare reform and raising the state pension age, could have been more effective.

Then there’s the eye-catching cuts to National Insurance, which cost over £10bn.

Cutting rates on National Insurance is forecast to add an extra 28,000 people to the workforce and lift the total hours worked by 94,000, the OBR estimates.

So all moves in the right direction, but by spending all of the extra inflation windfall in one go, its hard to avoid the conclusion that Hunt has taken a big gamble.

“I’m not sure I’d want to be the chancellor inheriting this fiscal situation in a year’s time,” Johnson said.