By Hans Nicholas Jong

JAKARTA — In 2015, Indonesian forestry giant Asia Pulp & Paper announced it would retire thousands of hectares of its commercial timber plantation in Sumatra, with the ultimate goal of restoring the land back to the tropical peat swamp it once was.

The ambitious project marked a notable shift in the forest management practices of APP, which had been heavily criticized in the past for draining and clearing large swaths of carbon-rich peat forests to plant the acacia trees from which paper, packaging and many other consumer products are made.

Central to APP’s effort was rewetting: the company had dug canals throughout the peat landscape to drain the waterlogged soil. Now it needed to do the reverse, blocking those same canals to allow the land to once again retain water.

And it seems to have worked, according to a newly published study in the journal Scientific Reports. Nearly a decade since the start of rewetting, soil carbon emissions have gone down, while native trees have sprung up, write the international group of scientists behind the study.

“We demonstrate that restoration through canal blocking has led to an enduring rise in the water table and initial recovery of the former vegetation cover through the re-establishment of native PSF [peat swamp forest] tree species,” they write.

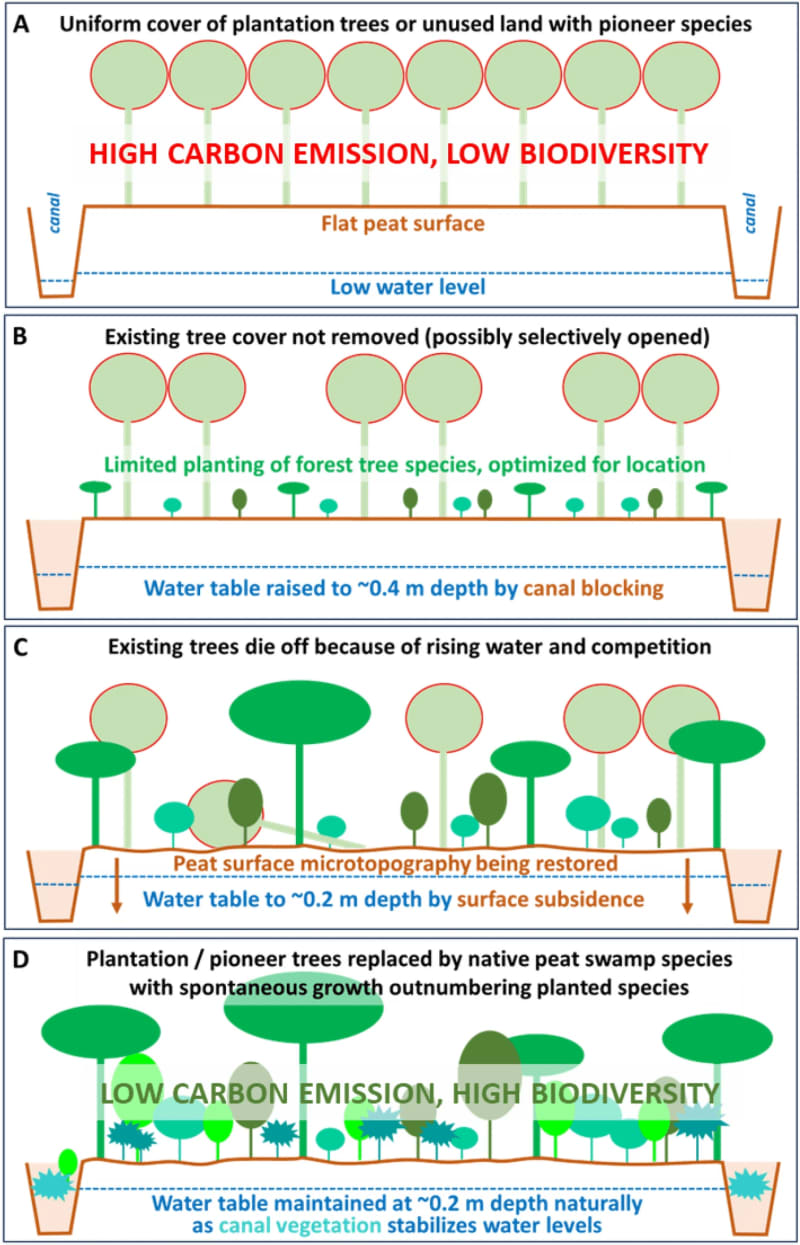

And once the canals were blocked, they add, nature required little help from humans: “The only active interventions are [i] canal blocking for moderate rewetting that avoids inundation where possible, [ii] limited local removal of existing non-native tree cover, and [iii] possibly ‘enrichment’ planting of PSF species in areas far from remaining forest.”

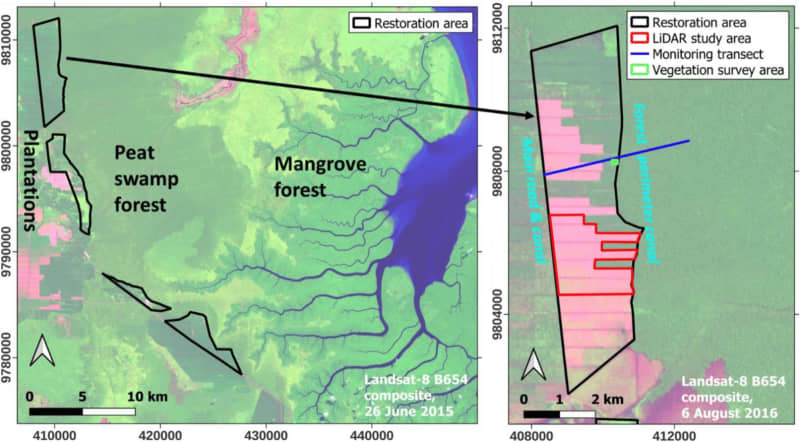

Location of the study area within the broader landscape in South Sumatra, Indonesia. The remaining peat swamp forest (PSF) and mangrove is mostly in Sembilang National Park.

More water and trees, less emissions

The researchers monitored the restoration area, spanning 4,800 hectares (11,900 acres) in Indonesia’s South Sumatra province, for seven and a half years. As part of APP’s retirement of the area, the company built 257 peat dams to block the canals.

The result? The water table rose by 30 centimeters (12 inches), while rates of land subsidence — the sinking of the sponge-like peat layer as a result of draining — slowed from a high of 7 cm (2.8 in) per year to about 1.5 cm (0.6 in) per year.

And since peat decomposition releases carbon emissions, the reduction in the peat surface subsidence rate led to reduced carbon emissions of 6.4 to 23.6 metric tons per hectare per year, the researchers estimated.

The researchers also found 57 native tree species had grown spontaneously in the most rewetted conditions and in high densities. And half of the restored no longer had acacias, indicating that even without human-led tree planting, forest regrowth is underway. The native tree species appear to do well with the higher water table, and are poised to replace the acacia pulpwood trees that don’t grow well in wet peatlands.

“[U]nassisted native tree recruitment and forest regrowth, further peat surface adjustment by subsidence, and canal vegetation development to complete the blocking process, will occur spontaneously after the initial rewetting intervention,” the researchers write.

However, they caution against expecting too much too fast, saying the slow growth rate of the native trees “indicates that full restoration to something similar to the original natural ecosystem cannot be a rapid process and may take some decades.”

Visual summary of steps in restoration as identified in the study, highlighting the interactions between rewetting and peat swamp forest restoration, jointly resulting in nature-based carbon emission reduction and ecosystem enhancement.

Replicable and scalable

The study notes that given that at least 1.2 million hectares (2.96 million acres) of plantations — pulpwood, oil palm and others — have been established on peatlands of similar characteristics in Sumatra, “It follows that the potential for application of the rewetting method evaluated in our study could be several million hectare at least, should plantation owners aim to restore forest in parts or all of their peatlands.”

The potential for replicability and scalability is echoed by Aida Greenbury, who was the managing director of sustainability at APP when the retirement and rewetting program started in 2015, and today serves as an independent expert. (Editor’s note: Greenbury sits on Mongabay’s advisory council.)

She said the findings show that reducing peat subsidence and loss and reducing carbon emissions simply by rewetting peat is no longer just a theory.

“This study has greatly contributed to the new definition of ‘best practice peatland management,’ a goal I set 10 years ago,” Greenbury told Mongabay, adding that other businesses can and should do the same.

“It is now clear that we need to protect remaining natural forests and peatlands, and it is important to restore converted peatlands adjacent to natural peat forests to maintain the integrity of peat landscapes, the carbon and biodiversity they support,” she said.

“Finally, it is imperative to strictly control peatland drainage and to replace existing commercial plant species that require excessive drainage with more flood-tolerant native species to reduce the adverse impacts on our environment.”

Citation:

Hooijer, A., Vernimmen, R., Mulyadi, D., Triantomo, V., Hamdani, Lampela, M., … Swarup, S. (2024). Benefits of tropical peatland rewetting for subsidence reduction and forest regrowth: Results from a large-scale restoration trial. Scientific Reports, 14(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-024-60462-3

Banner image: A blocked peatland canal built by villagers of Penyengat in Siak district, Riau province, Indonesia, as a part of research by CIFOR. Image by Hans Nicholas Jong/Mongabay.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay