You could once count on privacy as given. Even when PCs first became widespread in homes, they could serve as tools for this purpose. You could anonymously answer your most embarrassing questions using a digital encyclopedia or early online database.

But as internet usage rose, control over our personal information began to plummet. Now we’ve reached a stage where no one has complete say in the details shared about us—and more and more, tech products and services don’t just spill the beans, but they’re also digging deeper into our lives.

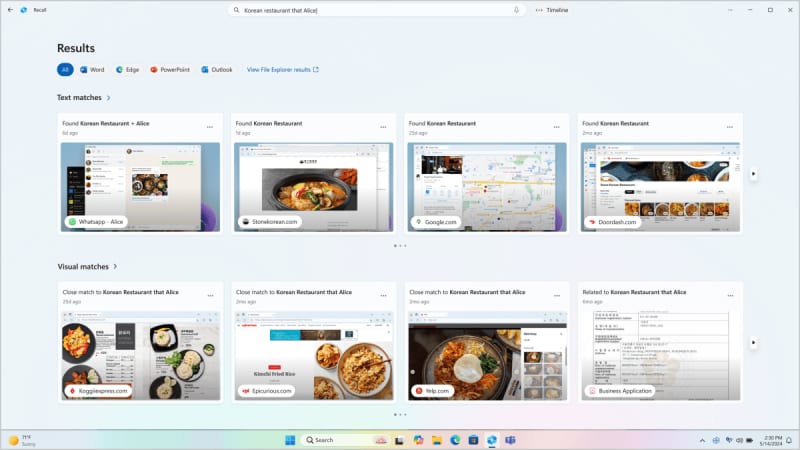

Take Microsoft Recall—a new feature with the potential to save hours of headache. When active, Windows captures screenshots of everything you do, then leans on AI to comb through that data when you want to find the recipe you looked at last week, or a message your coworker sent a few months ago. Essentially your PC surveils you, but for your benefit. And as announced, Microsoft Recall was on by default (for compatible PCs) and stored the data in a way that could’ve still allowed hackers to see all your activity if your system gets compromised. (Make sure you’re always running an active antivirus, folks.)

After fierce blowback, Microsoft quickly retooled Recall. The company set it to be off by default, required Windows Hello for use, and switched to decrypting the files only when accessed (aka just-in-time decryption). The speed of response was commendable, but also suggested Recall could have been announced in this incarnation from the start.

Microsoft

And so I’ve wanted to know why that didn’t happen—especially given how AirTags showed the dangerous ways that tracking technology can be used. Microsoft had the opportunity to learn from Apple’s slow reaction to the use of AirTags for stalking and then layer in the extensive knowledge it already has about online threats and data security. It chose not to.

Thirty years ago, the buoyant optimism of technology made sense. The world was less interconnected; access to the internet was new. Innovation could focus on the best-case scenarios. Much like small towns where front doors can be left unlocked, you could release fresh features with little concern that someone was going to exploit them.

Times have changed. I know the big tech companies are aware, as I’ve spoken to several recently about security. I’ve also talked with them about their efforts to broaden the voices at their tables and include more viewpoints. But inclusion isn’t just identity, but a diversity of experiences too. And either the design teams are lacking wide perspective or it’s being overridden, and that’s a shame.

Tempering optimism with realism doesn’t make for a weaker product. It broadens the appeal. Personally, I’m much more likely to try Microsoft Recall in its current form (whenever it launches, anyway). If a company takes clear steps to show they truly understand all the nefarious ways a technology can be used and have added in protections, I’m far more likely to try it.

Sometimes, it feels like the internet is now a sprawling metropolis—a place where you not only have to lock your front door, but sometimes add an iron gate in front of it (and perhaps over your bottom-floor windows, too). Any tech product or service that even touches on that connectivity is like a car that gets you around. But the people selling those cars don’t seem to listen when city folk tell them to empty their interiors before parking. Instead, they just add a steering wheel lock and are surprised when no one wants a car with broken glass.