Researchers at the University of Rochester have discovered a unique link between the reason we blink and our brain’s ability to process visual information.

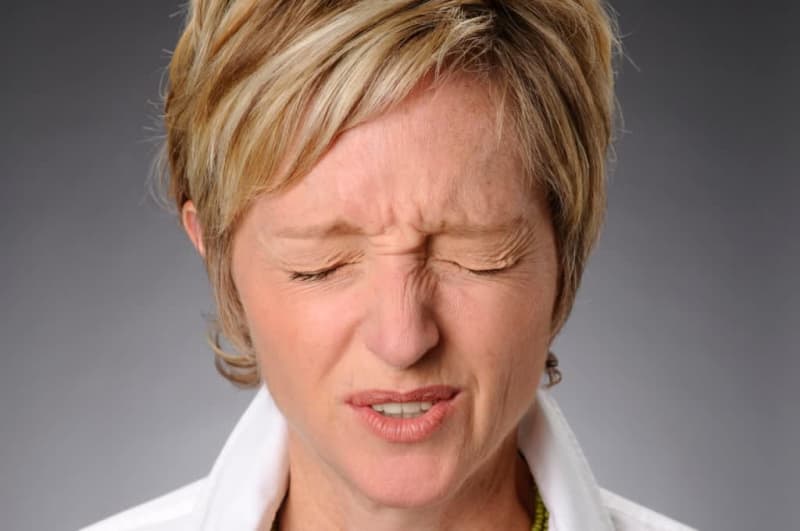

The human body is a miraculous thing, so much so that we are yet to discover all of its inner workings. While it has been previously understood that blinking serves to moisten the eye and remove dust, new research has suggested the reason for blinking goes much deeper.

The reason why we blink

Blinking is something practically everyone does, in fact, it’s believed that we spend 8% of our awake time with our eyes closed. Hoping to understand the function better, Michele Rucci and her team conducted a study using computer models, spectral analysis, and data from human participants. The researchers found that blinking is actually vital for our brains to process visual stimuli.

“By modulating the visual input to the retina, blinks effectively reformat visual information, yielding luminance signals that differ drastically from those normally experienced when we look at a point in the scene,” said the Department of Brain and Cognitive Science professor.

During the experiment, the scientists found that blinking enabled the participant to better assess changing patterns with varying levels of detail.

“We show that human observers benefit from blink transients as predicted from the information conveyed by these transients,” said Bin Yang, first author of the study. “Thus, contrary to common assumption, blinks improve—rather than disrupt—visual processing, amply compensating for the loss in stimulus exposure.”

What does this mean?

Besides being a fun little fact and providing you with a better understanding of the process, the study has highlighted the link between sensory input and motor activity. Though earlier research suggested sight was different, Rucci’s study suggests that sight is the same as other senses.

“Since spatial information is explicit in the image on the retina, visual perception was believed to differ,” said Rucci. “Our results suggest that this view is incomplete and that vision resembles other sensory modalities more than commonly assumed.”

Their findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.