Evidence of how new species evolve has emerged from two decades of research into cuckoos.

The theory of coevolution explains that when closely interacting species drive evolutionary changes in each other this can lead to ‘speciation’ - meaning the evolution of new species, but only now has real-world evidence of this been found by an international team of researchers.

They have been studying the evolutionary arms race between cuckoos and the host birds they exploit.

Bronze cuckoos lay their eggs in the nests of small songbirds and when the cuckoo chick hatches, it pushes the host’s eggs out of the nest.

The host bird loses its own eggs, and spends weeks rearing the cuckoo - when it could be breeding itself.

The host is fooled into accepting the imposter because each species of bronze cuckoo closely matches the appearance of its own chicks.

The researchers have found that new species can arise when cuckoos exploit different hosts. If a host rejects odd-looking nestlings because its own chicks have a distinct appearance, the cuckoo species diverges into separate genetic lineages that better mimic the chicks of its favoured host. These new lineages are the first sign that a new species is emerging.

“This exciting new finding could potentially apply to any pairs of species that are in battle each other,” said Prof Rebecca Kilner in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, a co-author of the report. “Just as we’ve seen with the cuckoo, the coevolutionary arms race could cause new species to emerge - and increase biodiversity on our planet.”

Chicks of different bronze cuckoo lineages have significant differences. These correspond to subtle differences in the plumage and calls of the adults, which help the males and females that specialise on the same host to recognise and pair with each other.

“Cuckoos are very costly to their hosts, so hosts have evolved the ability to recognise and eject cuckoo chicks from their nests,’’ said Prof Naomi Langmore, at the Australian National University, Canberra, lead author of the study published in Science.

“Only the cuckoos that most resemble the host’s own chicks have any chance of escaping detection, so over many generations the cuckoo chicks have evolved to mimic the host chicks.”

Coevolution is most likely to drive speciation when the cuckoos are very costly to their hosts, the researchers found, sparking a ‘coevolutionary arms race’ between host defences and cuckoo counter-adaptations.

“This finding is significant in evolutionary biology, showing that coevolution between interacting species increases biodiversity by driving speciation,” said Dr Clare Holleley, at the Australian National Wildlife Collection within CSIRO, Canberra, the senior author of the report.

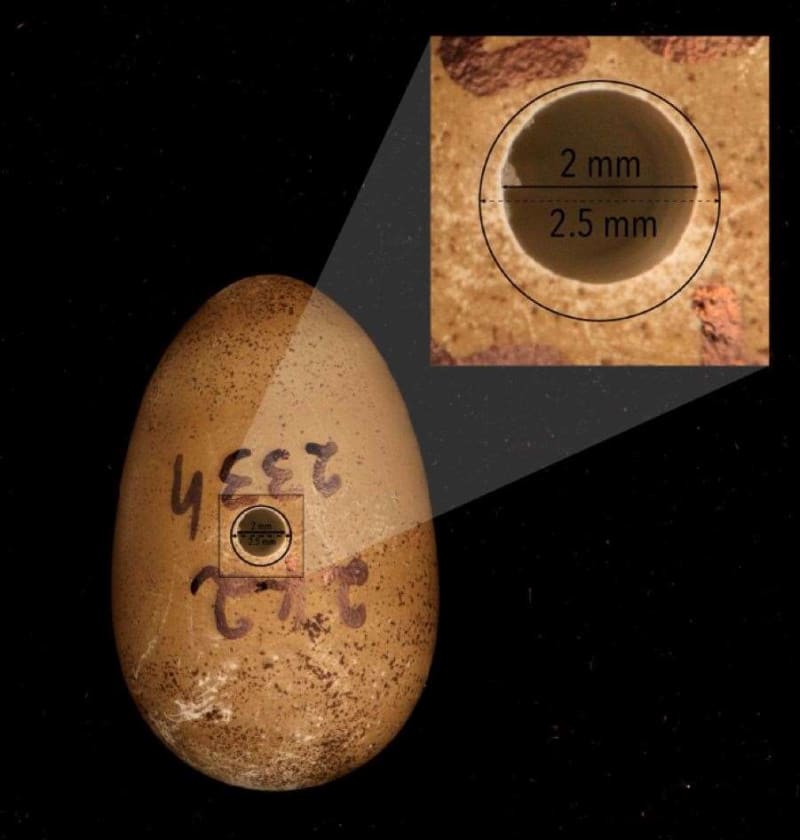

The study was possible thanks to a breakthrough by the team in extracting and sequencing DNA from eggshells in historical collections. DNA analysis of eggs and birds was combined with two decades of behavioural fieldwork.

The study involved an international team of researchers at the University of Cambridge, Australian National University, CSIRO (Australia’s national science agency), and the University of Melbourne. It was funded by the Australian Research Council.